How The Dedicated Freight Corridor Will Boost India's Export Economy

India has long sought to reduce logistics bottlenecks that raise trade costs. Logistics in India absorbs about 14–15% of GDP – well above the 8–10% typical of advanced economies – and India only ranks 38th in the World Bank’s 2023 Logistics Performance Index.

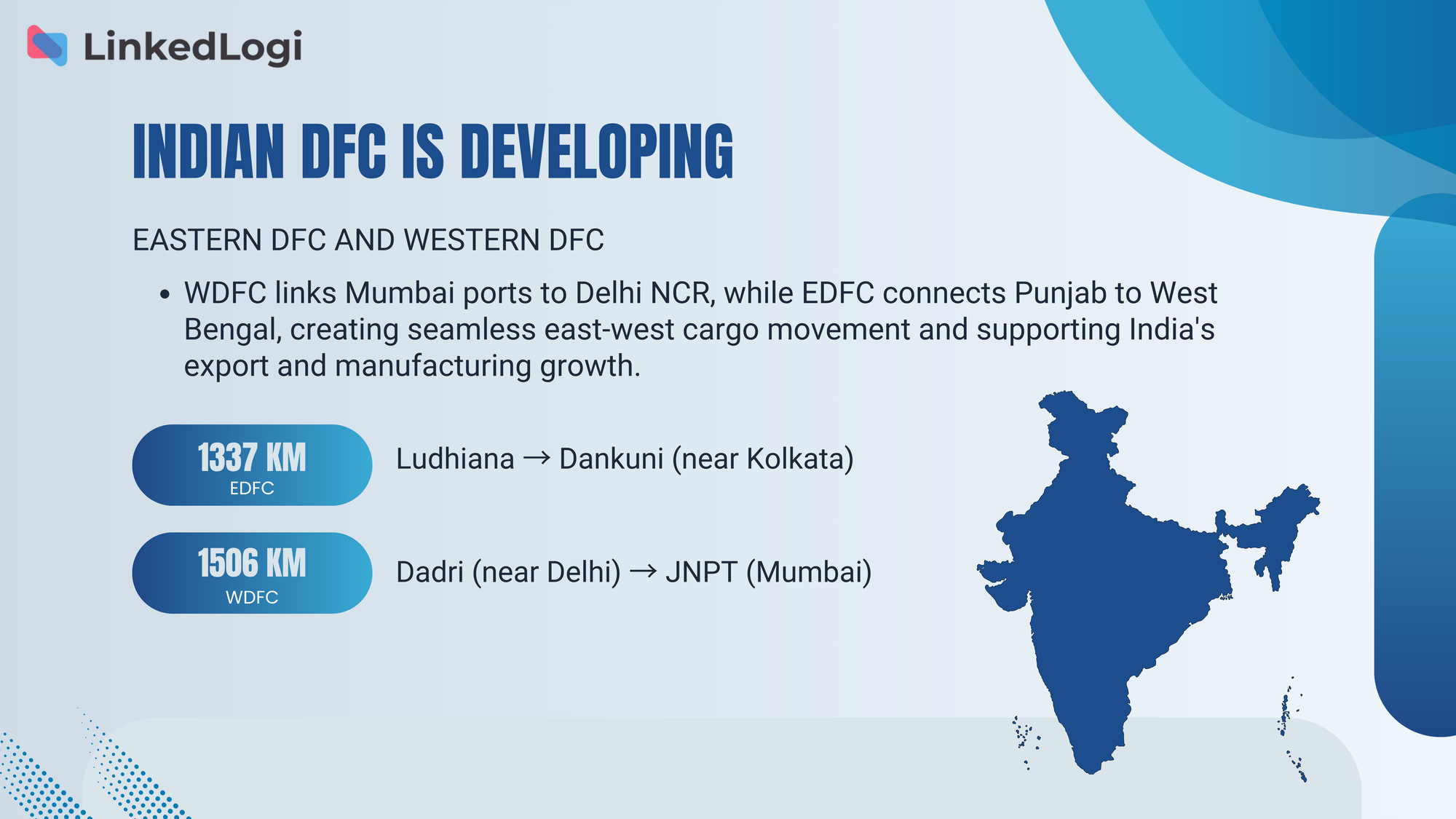

To boost exports and manufacturing, the government is rapidly completing two “Highways for Freight”: the Eastern Dedicated Freight Corridor (EDFC) and Western Dedicated Freight Corridor (WDFC). These are segregated, double-track rail lines carrying only cargo at high axle loads (25 tonnes) and speeds (designed up to 100 km/h). By moving bulk goods faster and more reliably from factories to ports, the DFCs are expected to cut transit times, lower costs and open new industrial clusters.

Eastern & Western DFC – Routes and Status

The Western DFC (WDFC) links India’s western ports to the industrial north and Delhi region. From Dadri (Uttar Pradesh) it swings west through Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat, terminating at Mumbai’s Nhava Sheva (JNPT). Branch lines serve Hazira and Mundra ports in Gujarat. The Eastern DFC (EDFC) runs from Ludhiana (Punjab) southeast through Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand to Son Nagar/Dankuni near Kolkata. (Dankuni is an outer Kolkata goods terminal connected to Haldia and Kolkata ports.)

By early 2025 about 96.4% of the 2,843 km of planned DFCs had been commissioned. All 1,337 km of the EDFC is operational, and roughly 1,500 of 1,506 km of WDFC is complete. This high completion rate came from coordinated funding and fast land acquisition. The DFCs are fully electrified (2×25 kV) and built for 100 km/h operation, far above the ~25 km/h average of conventional freight trains. This means block trains of 100+ wagons can run non-stop, carrying double-stack containers and heavy bulk (coal, steel, minerals) at high speed. For example, test runs on the Bhaupur–Khurja (EDFC) section averaged ~99 km/h while hauling coal. The corridors also integrate with India’s Gati Shakti plan: dozens of new multimodal freight terminals (Gati Shakti Cargo Terminals and Inland Ports) are being developed along the lines to link rail with road, ports and airports.

Efficiency and Capacity Gains

Electric freight trains on dedicated routes can carry hundreds of containers at once. The DFCs’ modern tracks and long loops allow high-speed, long-train operations (as above on the Eastern ghats). This sharply boosts throughput and cuts costs compared to mixed-use lines.

The DFCs have dramatically improved freight throughput and speed. With congestion cleared from traditional routes, Indian Railways can run many more trains per day. In FY2023-24, DFCCIL commissioned 1,272 km and saw a 42% jump in daily DFC trains, from 170 to 241 per day. By early 2025 that figure had climbed to ~350 trains per day on the corridors. Correspondingly, the total freight moved (gross tonne-km) on the corridors climbed to 119 billion GTKMs in 2023–24 (with 66.7 billion net tonne-km) – roughly triple the previous year’s volumes. In short, a minor share of track (4% of Indian Railways’ network) is carrying ≈10% of freight.

Key efficiency improvements include:

Much higher speeds: Trains regularly run at 50–60 km/h on DFC sections (with trials up to 100 km/h), compared to ~20–25 km/h on mixed routes. In practice this can halve transit times. For example, coal coal from Jharkhand to Ludhiana now moves hours faster, and freight from western ports to Delhi is reported to take roughly half the time on WDFC vs. old lines.

Longer/heavier trains: The 25-tonne axle load and long loops allow 150+ wagon trains. At full design capacity the two corridors could handle ~300 trains per day, vastly more than conventional routes.

Lower operating costs: Faster, continuous movement and double-stacking slash per-ton-km rail costs. DFCCIL projects that DFC operations will reduce logistics costs by boosting rail’s share of freight (from ~27% now toward 45% by 2030). (The National Logistics Policy explicitly targets cutting logistics costs from ~14% of GDP toward ~10%.)

Decongestion of legacy lines: By shifting ~50% of freight trains onto the DFCs, many passenger routes free up capacity. This improves on-time performance for all trains and allows IR to add new passenger and parcel services. (DFCCIL notes that in 2024–25 the corridors diverted so much traffic that punctuality and revenues rose across the network.)

Port Access and Multimodal Links

A central export benefit is seamless port connectivity. The WDFC directly serves western ports: from the Delhi region it heads straight to JNPT (Mumbai), with branch spurs to Hazira, Mundra and Kandla. This gives industrial centers (Gujarat, Delhi NCR, northern India) fast double-stack rail access to those major ports. The Eastern DFC, ending near Dankuni, connects eastern industries and mineral regions (Jharkhand, Odisha) to Kolkata–Haldia port terminals. New freight terminals on both corridors link to highways, inland waterways and airports. For example, India’s Gati Shakti Cargo Terminals at Khurja, JNPT and elsewhere enable quick transfer between rail and road containers.

These connections are already unlocking trade. Ports operated by DFCCIL partners (e.g. PSA Mumbai at JNPT) note that rail loading has surged since corridor links opened. North Indian exporters can now send goods straight to ports on dedicated tracks, avoiding toll roads and line congestion. Commodity and container throughput at connected ports is rising: ports saw 5% annual CAGR in tonnage (FY2015–19) even before full DFC service. As the corridors fill out, exporters across steel, coal, fertilizers and engineered goods will ship faster. By giving industry door-to-door rail service, the corridors integrate supply chains – a boon for time-sensitive exports like automobiles, textiles and electronics.

For instance, western India’s auto and electronics clusters (Gujarat/Rajasthan/Maharashtra) now have more reliable rail routes to JNPT and Mundra. Northern grain and sugar producers can route loads quickly to Vizag and Kolkata terminals. Textile hubs in Haryana/UP gain better access to east-coast ports. In all, the DFCs improve first/last-mile links and cut bottlenecks at port yards, directly supporting export sectors.

Impact on Key Sectors and Regions

DFCs benefit a wide swath of India’s economy. Industrial corridors along the routes host automotive, steel, cement, petrochemical and fertilizer plants. Faster rail cuts supply-chain costs for manufacturers: e.g. domestic auto majors moving vehicle parts or finished cars pay less in transit. In agriculture, bulk commodities (grains, sugar, cement and fertilizer) can now move en masse to ports or to inland logistics parks on faster timetables. The corridors also spur new economic zones: many government-backed Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and logistics parks are being located near DFC stations. In the textile sector, yarns and garments from North India can reach seaports in days instead of weeks.

In Southern India (which currently lacks a dedicated freight corridor), studies have noted huge export potential if a corridor were built. One analysis projects that a Chennai–Ennore–Krishnapatnam–Bengaluru rail corridor could carry 50% of the region’s exports, led by autos and electronics. Today, southern exporters rely on congested shared lines; similar benefits are expected when future DFCs (see below) link southern industries to coast ports.

Overall, the DFCs are rebalancing modal share. Rail’s freight share in India has stagnated below one-third; by contrast China and the US move far more freight by rail. NITI Aayog and industry note that better rail links encourage shippers to shift from trucks, cutting costs and emissions. This competitive rail service is vital for export competitiveness: for example, Indian exporters at major ports now see more predictable lead times thanks to dedicated rail corridors, an advantage over neighbors.

Global Benchmarks and Logistics Context

Although still evolving, India’s freight corridors are closing the gap on global leaders. The World Bank’s 2023 LPI ranks India 38th overall, up markedly from 54th in 2014, reflecting better infrastructure and digital reforms (ULIP, Logistics Data Bank). Rail-specific indices lag: Indian ports handle far fewer containers than China/USA, and Indian rail freight (tonne-km) is a fraction of China’s. The new corridors aim to remedy this.

India’s goal to cut logistics costs to ~10% of GDP by 2030 requires more efficient rails. By comparison, European nations spend ~8% of GDP on logistics and achieve high LPI ranks. Dedicated freight networks in countries like China and Japan have been key to their export growth. India’s DFCs – while smaller in length – adopt those best practices (heavy axle loads, long trains, electrification). Early results (speed, capacity, cost gains) suggest India is on track to meet international benchmarks for rail freight.

Future Corridors and Economic Prospects

The success of EDFC/WDFC has spawned plans for more corridors. Detailed Project Reports are being prepared for an East–West DFC (linking Dankuni/Kolkata to Palghar/Mumbai via Nagpur) and an East–Coast DFC (Kharagpur to Vijayawada). A north–south feeder (Vijayawada–Nagpur–Itarsi) is also under consideration. These would tie India’s large eastern and southern economies into the freight network. (A dedicated southern corridor connecting Chennai, Tuticorin, Kochi and Mangaluru has been proposed by industry groups.)

Projected impacts of these expansions are large. They would bring rail connectivity to ports like Vishakhapatnam, Chennai and Kochi, and open hinterlands (Andhra/Tamil Nadu/Kerala/Karnataka) to high-speed cargo flows. For example, an East Coast DFC could quickly link Odisha’s ore and coal industries to export hubs, while an East–West line would decongest existing routes between Kolkata and Mumbai. Analysts expect new corridors to similarly spur regional exports, encourage SEZ development, and lower supply-chain costs nationwide.

In sum, India’s Dedicated Freight Corridors are a transformative infrastructure investment. By 2025, India will have two operational freight-only railways across its breadth, enabling faster door-to-door shipment of export goods. Early data show sharply higher throughput, speed and rail mode share. As remaining sections and future corridors come online, India can expect a significant boost to its export economy via lower logistics costs, better port access and more efficient supply chains.